Metastatic Melanoma

Case History

History of Present Illness

G.H. is a 69 year-old man who presents with a long-standing history of intermittent left ear drainage, chronic left-sided otitis media and bilaterally decreased auditory acuity requiring hearing aids. The patient states that the drainage is straw-colored and associated with a ringing sensation in the left ear. He also complains of episodic imbalance that is present with movement and steadily worsening in severity over the past several months.

Most recently, G.H. is troubled by a firm, painful mass in the region of his left ear that has been progressively enlargening over the past month.

The patient reports onset of the earliest ear-related symptoms over a year ago, but denies any illnesses, trauma or other inciting events around that time.

Past Medical History

Right carotid aneurysm, hepatic encephalopathy secondary to sclerosing cholangitis, atrial fibrillation, hypertension.

Past Surgical History

Liver transplantation secondary to sclerosing cholangitis 1988

Cholecystectomy 1987

Knee replacement 1987

Appendectomy 1975

Medications and Allergies

Neoral and prednisone since transplant in 1987; coumadin; florinaf; metoprolol

NKDA or sensitivities

Family History

Negative for heart, liver and kidney diseases, diabetes and cancer.

Social History

The patient is a widower following his wife's death from metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. He denies past or present tobacco and alcohol use. He is currently retired and lives alone. He states that he is moderately active and enjoys walking, gardening and collecting antiques.

Review of Systems:

GENERAL: The patient denies any fevers or recent illnesses/infections. Energy, appetite, weight and activities are at baseline levels.

HEENT: He wears eyeglasses and denies any recent changes in vision, excessive tearing or diplopia. Ears are involved as per HPI. There is no epistaxis, nasal discharge or obstruction. Normal voice, no pain or dysphasia.

PULMONARY- F.M. denies cough, dyspnea, TB, reactive airway disease.

CARDIAC- He denies myocardial infarction, chest pain, rheumatic heart disease. He has been on coumadin for atrial fibrillation but has no palpitations.

GI- He denies nausea, vomiting, dysphagia or odynophagia and is having normal bowel movements.

GU- He denies any voiding-related symptoms.

CNS- F.M. denies stroke, seizure or paresthesias, but does describe gait imbalance.

Physical Examination

GENERAL: The patient is a well-developed, well-nourished Caucasian man who appears stated age and is in no acute distress.

SKIN:

- multiple actinic keratoses and nevi seen in sun-exposed areas

- solitary, hyperpigmented, 3-cm wide mass in left parotid area noted, firm and tender to palpation

- no other suspicious or palpable skin lesions are seen in the head and neck

- well-healed surgical scars on right abdomen.

HEENT and NECK:

- ophtalmologic exam is normal

- no nasal mucosal masses or lesions are seen

- bilateral hearing aids are present; right tympanic membrane and external auditory canal are normal, and patent tympanostomy tube is in place on left

- no oral cavity or oropharyngeal masses or lesions are seen

- three anterior teeth are in place, with more posterior teeth demonstrating severe gingival disease and extensive restoration.

NEURO: trigeminal and facial nerves are intact; gait unsteady, but cerebellar testing, muscle strength and Romberg's sign are all normal.

The remainder of the physical exam is within normal limits.

Data

LABS: CBC and chemistry panel are within normal limits.

IMAGING: Plain radiographic films of the skull and soft tissues of the neck are negative. Head CT scan is also negative, except for the presence of a 3 x 3 cm left parotid mass with infiltration into subcutaneous tissues.

Plain films |

Head CT scans |

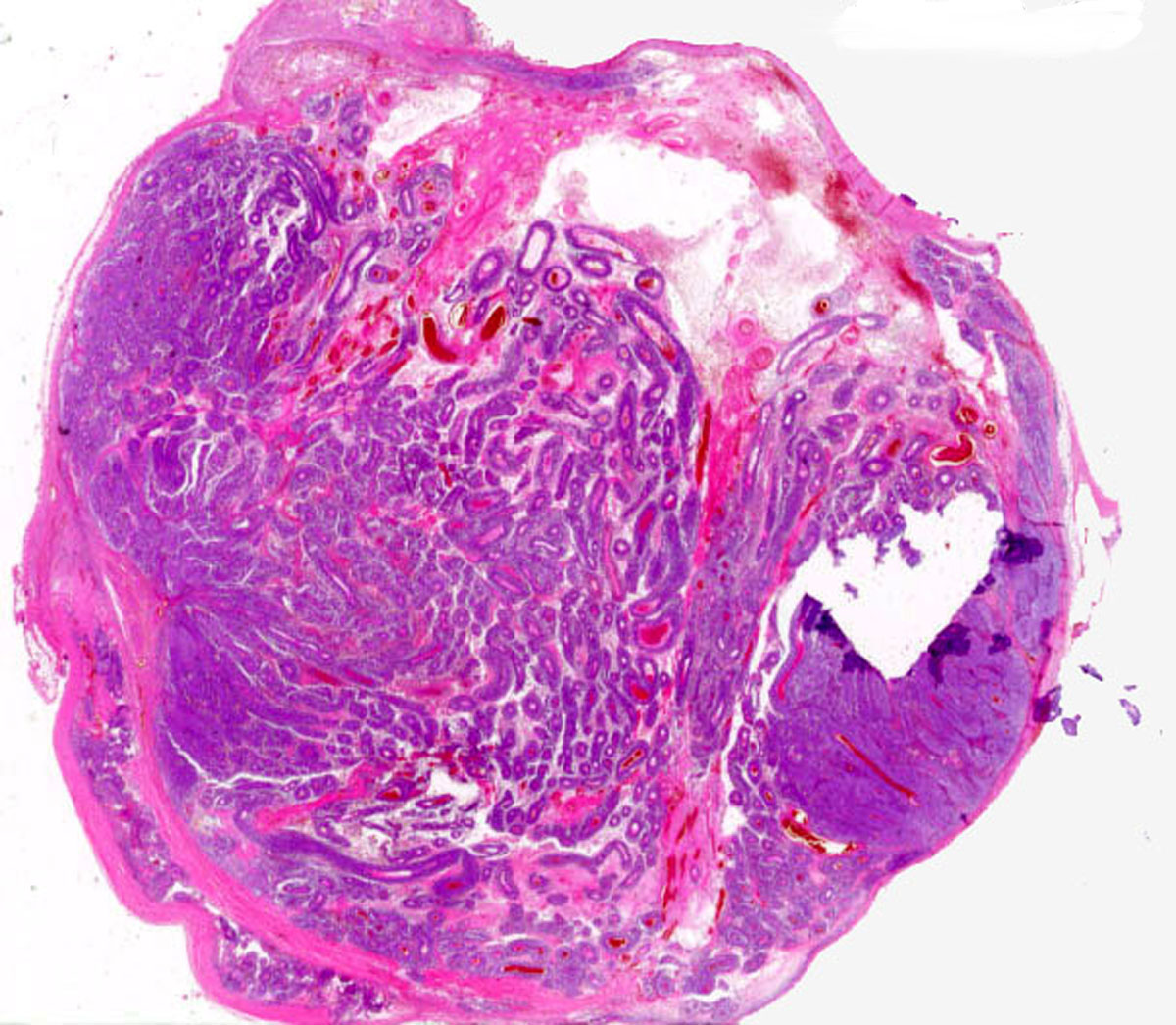

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES: Indirect laryngoscopy is negative for masses or lesions in the pharynx or larynx. There is normal vocal cord mobility. The fine needle aspiration biopsy of the left parotid mass is positive for melanoma.

Low-power microscopic view (H & E stain) |

Assessment and Plan

G.H. is diagnosed with facial cutaneous melanoma of the left parotid area, confirmed by pathologic findings from fine-needle aspiration biopsy. As the locoregional imaging and systemic staging studies both suggest localized disease, surgical excision of the primary tumor is considered the procedure of choice. The risk for recurrence and need for adjunctive radiation therapy will then largely be determined based on intraoperative findings, including the level of local invasion, the status of lymph nodes and the adequacy of margins obtained post-excision. The patient is counseled on his options and opts to proceed with surgery.

Clinical Course

The patient is taken to the operating room for a left parotidectomy, neck dissection and reconstruction. The mass measures 4 x 3 x 3 cm in the left parotid and infiltrates the subcutaneous soft tissues. Negative margins of resection are obtained, and all excised lymph nodes appear tumor-free. The tumor histology is read as pre-amorphic. However, given the infiltration of subcutaneous tissues in the parotid area, as well as his ongoing intake of immunosuppressive drugs, which may have predisposed him to tumor development in the first place, the G.H. is felt to be at high risk for local regional recurrence.

Consequently, he is counseled on the indication for postoperative radiation therapy, which has been shown in retrospective series to improve local regional control. However, there is no data at present indicating improved survival with these measures, thus the patient is referred to a dermatology pigmented lesion clinic for thorough skin examination as well as evaluation for possible further treatment with systemic agents.

The patient is seen by a radiation oncologist, who assigns him an ECOG performance status of zero. G.H. receives hypofractionated radiation treatment for a total of 30 cGy in 5 fractions, given twice weekly. Overall, he tolerates the therapy well and is without major complaints.

Three months following completion of the adjuvant radiation therapy, G.H. is seen in the office for a follow-up appointment. At this time a right mid-face 1-cm nodule is noted. Biopsy is positive for melanoma, but systemic staging is again negative. The patient undergoes wide local excision, right-sided parotidectomy, and an upper neck dissection. Surgery reveals the presence of a 2-cm metastatic melanoma with an initial deep margin less than 1 mm and negative lymph nodes. The parotid parenchyma is otherwise negative.

At this point, the medical oncologist does not recommended further treatment. Also, since the final margins were negative and there was no clear antecedent skin lesion, thus possibly representing an internal metastasis, the radiation oncologist does not feel that radiation is necessary. However, the surgical oncologist feels very strongly that the patient is at extremely high risk for local regional recurrence and recommends radiation therapy. To support his argument, he cites two main facts: firstly, the patient's parotid tumor is deeply infiltrative, with skin potentially being an independent primary source, and secondly, the initial margin was positive. Futhermore, if the facial melanoma were to recur, there would be limited salvage opportunities, or even palliative potential, available at that point.

The patient agrees with the surgeon and requests radiation therapy. At this time, the patient is doing very well systemically. His energy, appetite, weight, and activities are stable. He denies tobacco and alcohol use, and he is performing actinic protection.

Within two months of the right facial surgery, the right parotid tumor bed is treated over 14 days with a 12 MEV electron beam, using en face technique. The total tumor dose is 3000 cGy in 5 treatment fractions. The patient tolerates the course of therapy relatively well. The patient does develop mild right buccal discomfort with mild xerostomia, and thus is put on Salagen with a good response.

G.H. is scheduled for regular follow-up with his surgeon, dermatologist and radiation oncologist.

Discussion

Advanced melanoma is refractory to most standard systemic therapy, and all newly diagnosed patients should be considered candidates for clinical trials. Deciding on further treatment depends on many factors, including prior treatment and site of recurrence, as well as individual patient considerations.

Surgery is the most efficacious therapy for localized recurrence in sites where it can be accomplished (including lymph node, skin, brain, lung, liver, and gastrointestinal sites) [1]. Although advanced melanoma is relatively resistant to therapy, several biologic response modifiers and cytotoxic agents have been reported to produce objective responses.

The objective response rate to dacarbazine (DTIC) and the nitrosoureas, carmustine (BCNU) and lomustine (CCNU), is approximately 20% [2]. Responses are usually short-lived, ranging from 3 to 6 months, although long-term remissions can occur in a limited number of patients who attain a complete response [2]. Other agents with minimal single agent activity include vinca alkaloids, [2] platinum compounds, [2] and taxanes [3]. Phase II studies of 3-drug combinations showed higher response rates than were seen with single agents, ranging from 25% to 45% [4,5]. Randomized trials comparing these combination regimens with DTIC have not consistently demonstrated any advantage for the combination, although these trials had limited sample sizes and insufficient power to detect small but clinically relevant differences in response or survival [6,7,8,9]. The addition of tamoxifen to the triple-drug combination regimen of cisplatin, BCNU, and DTIC showed high response rates in phase II studies, with a 20% complete response rate in several trials [10]. A phase III trial testing the 3 drugs with and without tamoxifen showed no benefit for the addition of tamoxifen, and the response rates for both study arms were once again in the 20% to 25% range [10]. An ongoing trial is directly comparing DTIC alone to the 3-drug regimen plus tamoxifen [11]. Pending results from ongoing trials, no combination regimen has proven superior to DTIC alone.

The two biologic therapies that appear most active against melanoma are interferon alfa (IFN-A) and interleukin-2 (IL-2). Response rates for IFN-A range from 8% to 22% and long-term administration on a daily or a 3 times per week basis appears superior to once per week or more intermittent schedules [2,3]. Response to IL-2 regimens is similar, in the 10% to 20% range [3]. Attempts to improve on this with the addition of lymphokine-activated killer cells, autologous lymphocytes activated by IL-2 ex vivo, and by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, lymphocytes derived from tumor isolates cultured in the presence of IL-2, have not improved response rates or durable remissions sufficiently to merit the expense and complexity of these therapies.

Phase II studies testing combinations of IFN-A and IL-2 have demonstrated high response rates, but a phase III comparison of IFN-A and IL-2 compared with IL-2 alone in 85 patients did not show any benefit for the combination [3].

Combinations of chemotherapy and biologics (such as chemoimmunotherapy or biochemotherapy) have been tested against chemotherapy alone. Four small phase III studies comparing DTIC and IFN-A with DTIC alone have shown conflicting results [10]. A larger trial testing this question has completed patient enrollment, but results are not yet available.

IL-2 has also been combined with cisplatin in several phase II trials [12, 13, 14] with very encouraging response rates, but data supporting an improvement in survival are lacking. Two ongoing phase III trials are comparing complex biochemotherapy regimens (IFN-A, IL-2, and chemotherapy) to chemotherapy alone. Pending the results of these and future trials, there is no proof that biochemotherapy is superior to chemotherapy.

Although melanoma is a relatively radio-resistant tumor, palliative radiation therapy may alleviate symptoms. Retrospective studies have shown that patients with multiple brain metastases, bone metastases, and spinal cord compression may achieve symptom relief and some shrinkage of the tumor with radiation therapy [15,16]. The most effective dose-fractionation schedule for palliation of melanoma metastatic to the bone or spinal cord is unclear, but high-dose-per-fraction schedules are sometimes used to overcome tumor resistance.

Treatment options

:

- Resection of isolated single or localized metastases from skin, visceral, or brain sites in selected patients is sometimes associated with prolonged survival.

- Palliative radiation therapy for bone, spinal cord, or brain metastases.

- Palliative biologic therapy and/or chemotherapy in phase I and II clinical trials.

- Palliative treatment with interleukin-2 or interferon can occasionally result in prolonged survival.

Referencias

1. Wong JH, Skinner KA, Kim KA, et al.: The role of surgery in the treatment of nonregionally recurrent melanoma. Surgery 113(4) 389-394, 1993.

2. Legha SS: Current therapy for malignant melanoma. Seminars in Oncology 16(1, Suppl 1): 34-44, 1989.

3. Sparano JA, Fisher RI, Sunderland M, et al.: Randomized phase III trial of treatment with high-dose interleukin-2 either alone or in combination with interferon alfa-2a in patients with advanced melanoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 11(10): 1969-1977, 1993.

4. Rosenberg SA, Lotze MT, Muul LM, et al.: A new approach to the therapy of cancer based on the systemic administration of autologous lymphokine-activated killer cells and recombinant interleukin-2. Surgery 100(2): 262-271, 1986.

5. Overett TK, Shiu MH: Surgical treatment of distant metastatic melanoma: indications and results. Cancer 56(5): 1222-1230, 1985.

6. Ahmann DL, Hahn RG, Bisel HF: Evaluation of 1-(2-choroethyl-3-4-methylcyclohexyl)-1-nitrosourea (methyl-CCNU, NSC 95411) versus combined imidazole carboxamide (NSC 45388) and vincristine (NSC 67574) in palliation of disseminated malignant melanoma. Cancer 33(3): 615-618, 1973.

7. Wittes RE, Wittes JT, Golbey RB: Combination chemotherapy in metastatic malignant melanoma: a randomized study of three DTIC-containing combination. Cancer 41(2): 415-421, 1978.

8. Chauvergne J, Bui NB, Cappelaere P, et al.: Chimiotherapie des melanomes malins evolues: resultats d'un essai controle comparant l'association de detorubicine et de dacarbazine (DTIC) a la dacarbazine seule. Semaine des Hopitaux (Paris) 58(46): 2697-2701, 1982.

9. Costanzi JJ, Al-Sarraf M, Groppe C, et al.: Combination chemotherapy plus BCG in the treatment of disseminated malignant melanoma: a Southwest Oncolgy Group study. Medical and Pediatric Oncology 10(3): 251-258, 1982.

10. Anderson CM, Buzaid AC, Legha SS: Systemic treatments for advanced cutaneous melanoma. Oncology 9(11): 1149-1158, 1995.

11. Meyers ML, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center: Phase III Randomized Study of CDDP/DTIC/BCNU/TMX vs DTIC Alone in Patients with Advanced Melanoma (Summary Last Modified 05/98), MSKCC-91140, clinical trial, closed, 12/29/1997.

12. Demchak PA, Mier JW, Robert NJ, et al.: Interleukin-2 and high-dose cisplatin in patients with metastatic melanoma: a pilot study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 9(10): 1821-1830, 1991.

13. Flaherty LE, Robinson W, Redman BG, et al.: A phase II study of dacarbazine and cisplatin in combination with outpatient administered interleukin-2 in metastatic malignant melanoma. Cancer 71(11): 3520-3525, 1993.

14. Atkins MB, O'Boyle KR, Sosman JA, et al.: Multiinstitutional phase II trial of intensive combination chemoimmunotherapy for metastatic melanoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 12(8): 1553-1560, 1994.

15. Rate WR, Solin LJ, Turrisi AT: Palliative radiotherapy for metastatic malignant melanoma: brain metastases, bone metastases, and spinal cord compression. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics 15(4): 859-864, 1988.

16. Herbert SH, Solin LJ, Rate WR, et al.: The effect of palliative radiation therapy on epidural compression due to metastatic malignant melanoma. Cancer 67(10): 2472-2476, 1991.